Discover more from Fresh Economic Thinking

Housing confusions: Builders versus property owners and building versus planning approval

Where I straighten out some strangely common confusions in housing supply debates.

In this post I straighten out some confusions that crop up in housing debates. Too much commentary and analysis overlooks that

building approvals and planning approvals are different, and

builders and developers are different.

I want to tick off the second of these before focussing in more detail on the first.

Builders don’t choose to build, property owners do

In the Australian context, builders are construction companies that erect buildings for clients who own the property where the building is to be built.

Sometimes, builders enter into contracts with property developers of large subdivisions. These contracts give builders the right to facilitate sales of lots owned by the developer as part of a package, whereby the customer enters a land purchase contract with the developer and a building contract with the builder.

Notice that the builder, even in this case, cannot build a home without a property owner making that decision. Builders rely on the decisions of the property owners.

New dwelling supply is therefore driven by the financial incentives of property owners, who want to maximise the total return on their property assets over time, not builders, who want to maximise housing construction turnover but can only do so subject to the decisions of property owners.

The incentives of builders and property owners are different. Sometimes the same company does both activities but this doesn’t change the underlying incentives.

In general, builders make about 10% margins on all costs. Their business is less risky. They get progress payments as they go, so capital exposure is limited. Property developers require margins of 20-30% and must raise a lot of funds to put at risk during the life of the project (which they minimise with staging and such). If prices fall, or construction costs rise, they carry that risk, hence the higher margin.

How much new housing is built is not a choice made by builders but by property owners. This is why the idea of property as a monopoly makes so much sense. Non-property owners can’t compete using non-property inputs. They must always buy property from a current owner to get into the housing game, and these current owners have no incentive to minimise the price they receive by rapidly increasing their sales or rapidly building new homes.

This means that arguments that rely on the nature of the building and construction industry to understand the competitive processes involved in new housing supply, such as in the below tweet, show a failure to understand decision-making in the housing market.

Only owners of property assets can choose to develop new homes, not builders.

Building approval is not planning approval

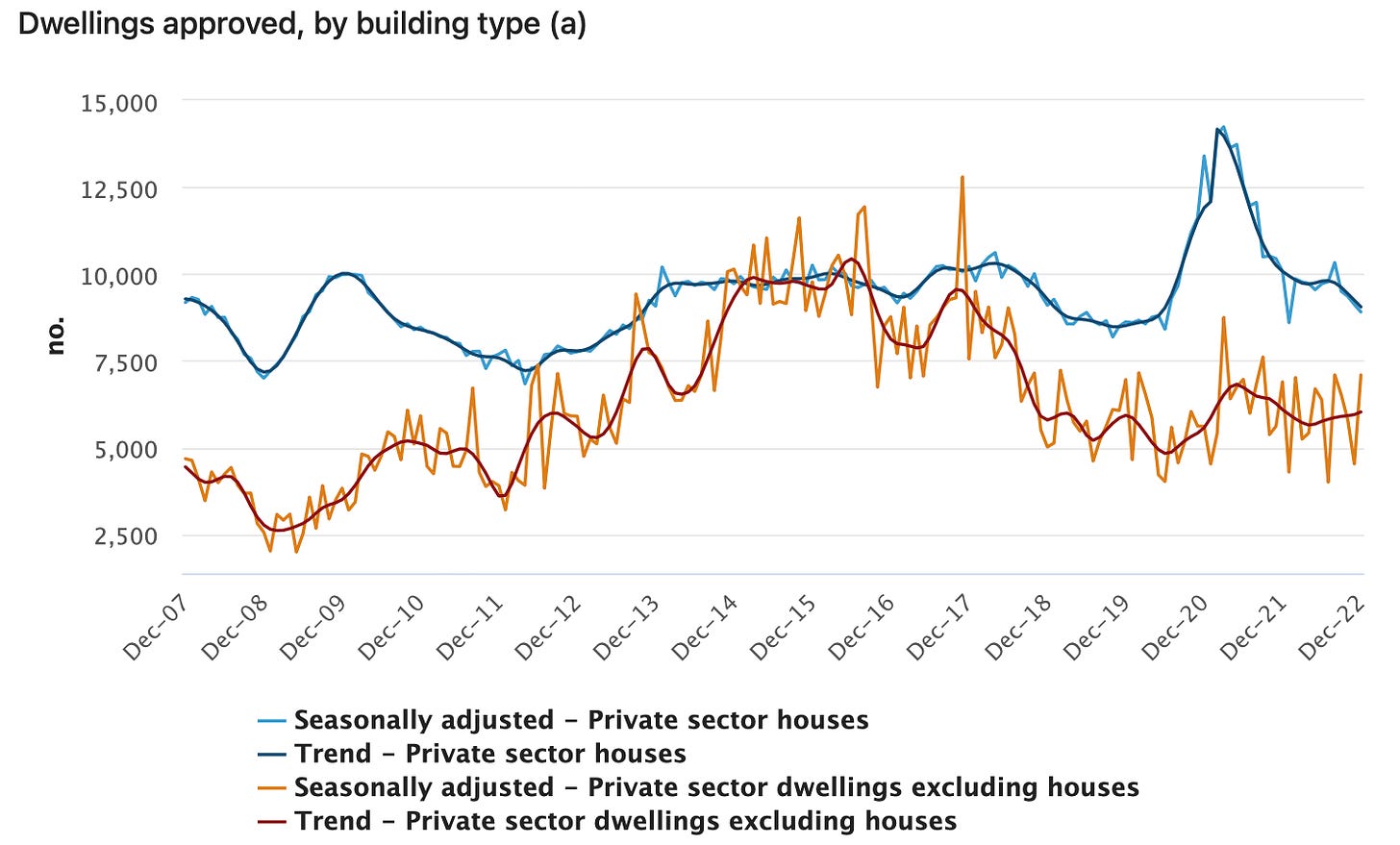

Another common confusion is assuming that the national statistics on building approvals, like in the image below, are thought to be approvals for new housing from the planning system.

They are not.

Building approvals (BA) are issued after assessing construction designs against the building code. A development approval (DA), or planning approval, is required when you want to subdivide a lot, horizontally or vertically, or change the type of use (even of an existing building). In Queensland, these two planning approval types are known as reconfiguration of a lot and a material change of use. For some developments, your planning application will be for both, and often an approval to carry out building work.

For a knock-down-rebuild project on an existing lot, you may need no planning approval at all.

Typically, the development process squeezes in pre-sales between these two approvals as follows:

Buy or option site → planning approval(s) → pre-sell dwellings, and if successful → building approval → build and then settle sales.

This is why I call the housing market build-to-order. It is no surprise that most building approvals get built because seeking building approval usually happens after a new dwelling is already sold. However, in some market conditions, such as a big price decline, the plug is pulled even on projects with building approval.

But a planning approval is different.

Many planning approvals are granted, only to lapse or be later modified. It is not uncommon for the same property to have a planning approval, then market that project but fail to get buyer interest, then reapply for a different approval, get that approval and fail in the market, and then sell the property to a new owner who seeks and is granted another approval, with all of this occurring over many years.

Notice only property owners or their representatives can apply for a planning approval and planning authorities can only approve or deny applications that are made.

Indeed, in Australia’s planning systems, property owners are able to seek approvals that fall far outside the zoning codes. If they choose to do so, they embark on a slower and more tedious assessment process. If they choose to comply fully with zoning codes, approvals typically must be granted and there are no rights to object (at least in Queensland). Many councils even have a fast-tracked process for projects that comply with codes and are under a certain size (often 5 dwellings) that guarantees approval within 5 days.

So if planning approvals rise or fall, this is generally because property owners are making more, or fewer, approval applications. If you would like to argue that a decline in approvals is somehow caused by planning regulations at a certain point in time, then when approvals rise these must also be credited to the same planning regulations.

It is possible to apply for many planning approvals and hold a stock of approved projects that allow the flexibility to quickly respond to the market. Many of the largest housing developers do this.

Where can I find the planning approvals data?

Unfortunately, there are very few aggregated records of planning applications or approvals. Most councils have their own online portals where you can search for applications and see all the documents and the back-and-forth process that often happens. Many of these portals are cumbersome to use. Brisbane’s is here, for example.

Because of the degree of complexity, there seems to be little interest in pulling this data together.

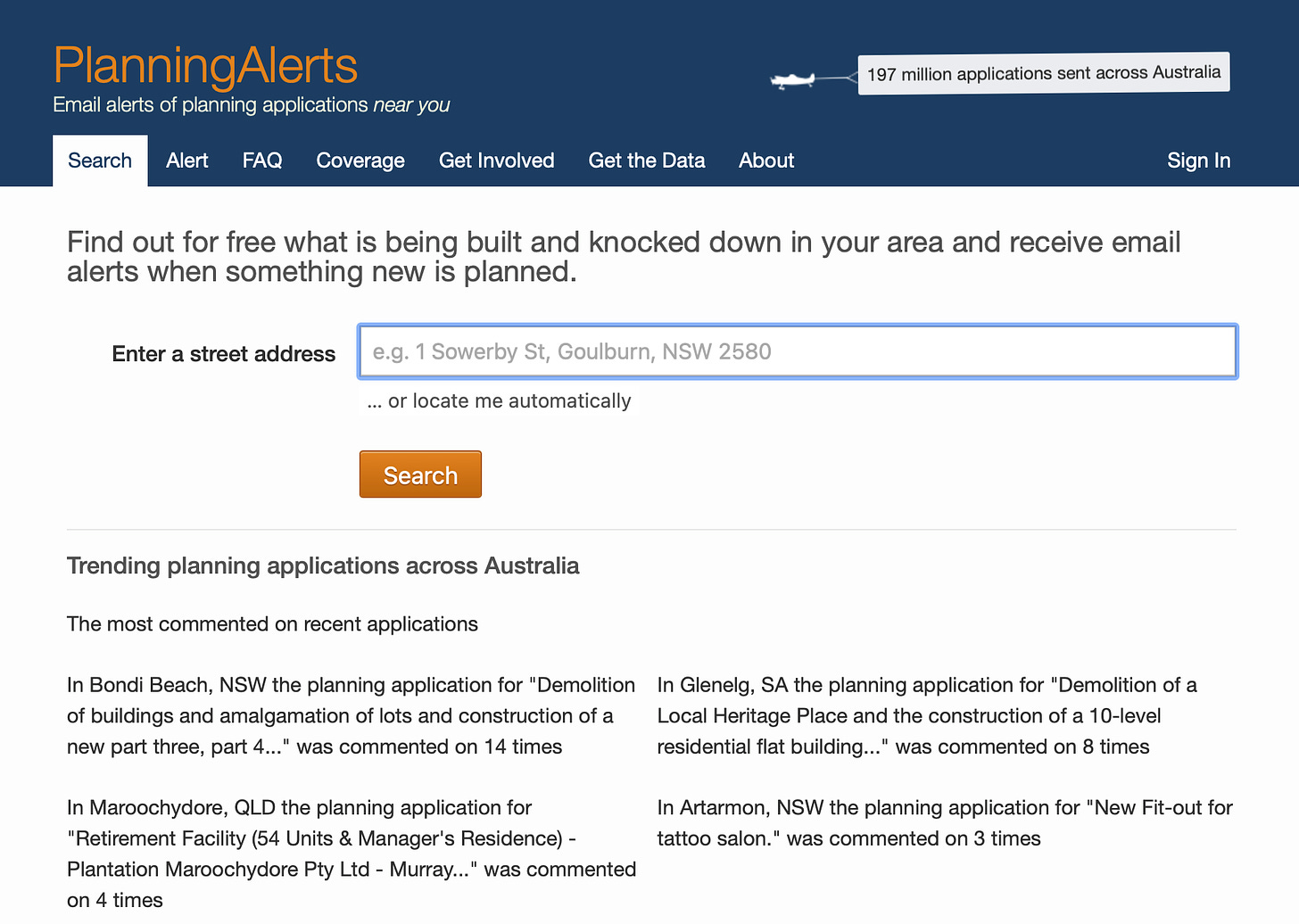

For those interested in browsing their local planning applications, you can keep track of applications made in your area with the terrific Planning Alerts site that scrapes many council planning portals for new applications (the list of councils is here).

You will notice when browsing these portals that the planning system does a lot more than just check if proposed housing projects comply with zoning codes. It allows for rather complex applications to be made by a property owner who wishes to develop in a way that conflicts with the planning (zoning) codes and enacts a process to check that these outcomes are reasonable.

This means that it is difficult to estimate things like zoned capacity or other ways of conceptualizing how the strictness of the planning system because the codes (zones) in plans are not hard limits. For example, a study in Los Angeles found that about half of new housing projects did not comply with zoning codes.

Even after accounting for bonuses, only about 55 percent of new units permitted from 2010 to 2020 fell within their parcels’ zoned capacity. The rest either involved changes in zoned capacity or exceptions to it.

One of the best attempts to track metrics of the planning system is in Queensland with the published Residential land development activity profiles (the latest spreadsheet up to Dec 2022 is here). These track the number of new planning approvals for detached residential lot subdivisions (reconfiguration of a lot approvals), the stock lots in approved subdivisions, the lapses of approvals, and the completion of these subdivisions.

Unfortunately, these do not track all applications, applications that are denied approval, the stock of approvals for attached dwellings, and more. But it’s the best we have so far and I’ve used this data in two of my research papers to demonstrate the lack of relationship between zoned capacity and new housing production.

What’s the rush? New housing market absorption rate metrics and the incentive to slow housing supply

As mentioned earlier, the data on building approvals lives at the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), which is now also collecting data on land and housing supply metrics. But these are again not exactly useful as they count building approvals and match them with planning zoning codes, which are themselves constantly changing and usually flexible.

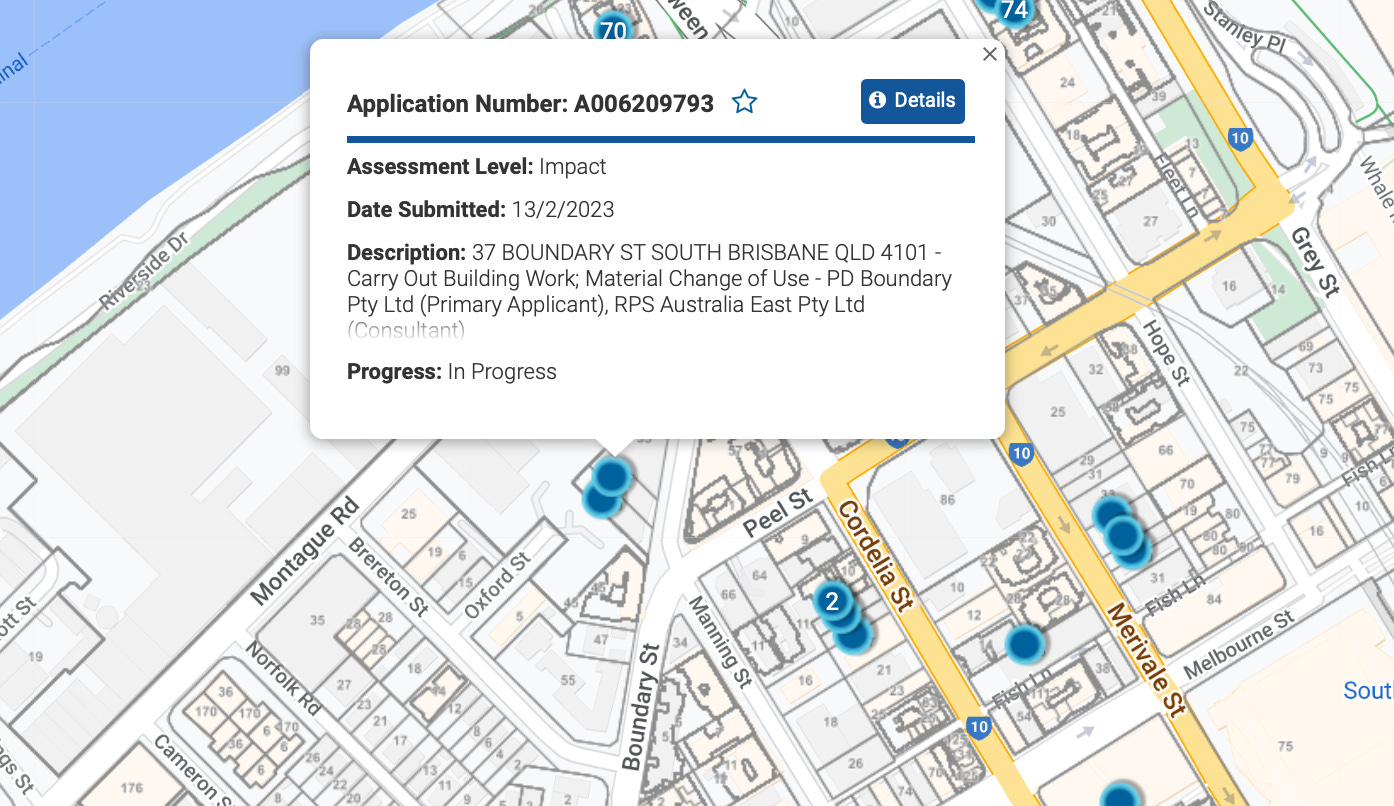

An example of a planning application that exceeds zoning codes

A recent application in my neighbourhood is a good example of how the planning system is more flexible than just the zoning codes. The site is 37 Boundary St, South Brisbane, and a planning application has been made for a 25-storey apartment tower in an area with a zoning code allowing for 20 storeys.

The property owner argues in their submitted report that an extra 5 storeys are reasonable given surrounding conditions, and I think that’s true. But the choice to design a 25-storey building and apply for this more difficult and slower approval, instead of a 20-storey building that would comply with the code, means they have chosen to risk community appeals.

In their submitted report we see their arguments for more density.

This is a 154-dwelling proposal that would have been about 123 dwellings if it complied with the zoned height limit. I fully expect it will be approved and that the suburb will have 33 extra dwellings on that site that apparently the planning regulations did not allow, or 22% more.

This type of flexibility is underappreciated in the analysis of planning regulations and housing supply. And it should be noted that the builder of this project has absolutely no say in the size or scope of the project. Only the property owner has. In fact, no builder has likely been involved at all yet in the project, and the project won’t seek a building approval probably for many years after pre-sales have been successful. And there is even the possibility that the project will be approved by the planning system but never built, and a new application made in the future.

It’s all about the dirt!

See here: https://myhomehousing.org.au/houses/

This is a great initiative to provide shelter for those who cant afford what is on offer in the residential zone. It began with an architect networking amongst those who could step up and make it happen. What this demonstrates is the gap between what people can provide themselves and what's required to create 35 square metres of basic accommodation for a single person and it also shows how costs can be shaved to achieve a result.

If rural landowners were allowed to site houses like the ones developed in Perth for this project, the accommodation shortage could be gradually overcome.

Currently rural landowners can apply to site cottages for short term tourist accommodation, a small market that doesn't yield a strong return because cottages tend to be empty between holiday periods. All that is required is to enable these cottages to be rented on a permanent basis rather than three months or whatever the local limit is.

A desirable feature of the cottages is that they are provided in a flat pack that can be assembled and disassembled in less than a day. So land can be lent out for a period without alienating it for long periods of time and creating a situation where it is difficult to redevelop to cater for changing needs.