Discover more from Fresh Economic Thinking

Downs-Thomson housing paradox

Roads are always congested, no matter how many are built. The same logic is why housing is always expensive, no matter how many are built.

Anthony Downs and various others made the observation that “the equilibrium speed of car traffic on a road network is determined by the average door-to-door speed of equivalent journeys taken by public transport.”

Though known as the Downs-Thomson (DT) paradox, it is not a paradox at all. It is merely an observation that people adapt their behaviours to road network changes that affect the cost of driving.

The basic idea is that there are three margins from which substitution towards peak hour use of new freeway capacity occurs.

many drivers who formerly used alternative routes during peak hours switch to the improved expressway (spatial convergence), and

many drivers who formerly travelled just before or after the peak hours start travelling during those hours (time convergence), and

some commuters who used to take public transportation during peak hours now switch to driving, since it has become faster (modal convergence).

This is a simple application of the logic of substitution in microeconomic consumer theory. If an alternative has a lower economic cost for the same value gained, people will substitute towards the lower-cost alternative. Consumer choices are what enables markets to select for the more efficient producers and mix of goods and services over time as they respond to relative prices.

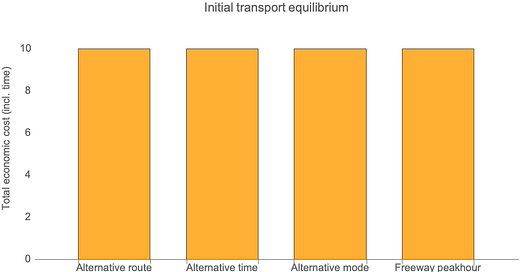

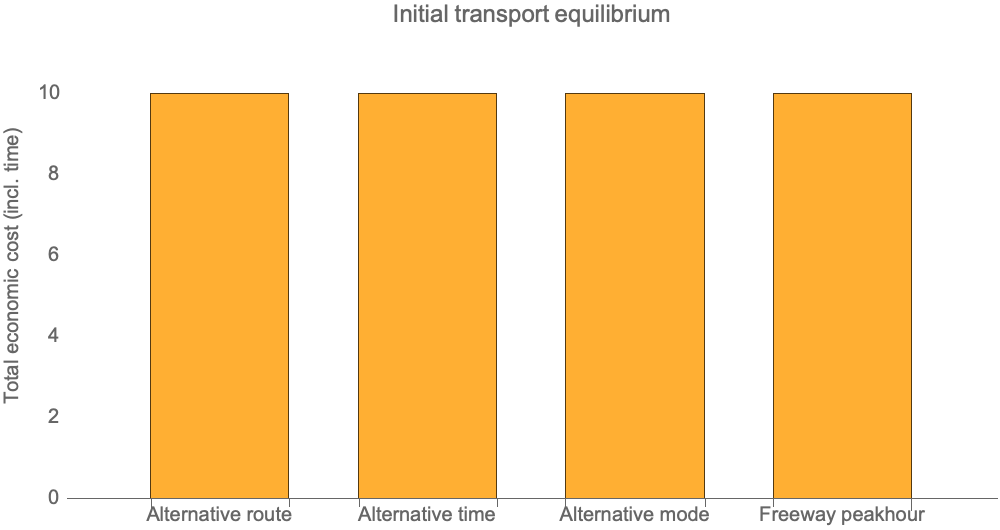

In the DT example, the three alternatives and the peak hour freeway use start at the initial equilibrium. Prior to the new freeway, all the transport alternatives are taken up to the degree that the total cost (time/money/convenience) is equalised across them.

The cost of travelling on an alternative route, or at an alternative time, or using an alternative mode, is roughly the same as the cost of peak hour freeway transport. It must be because if it wasn’t there would be a substitution towards the lower-cost option.

If you reduce the cost of one of these alternatives what happens? That option begins to look relatively attractive, and people substitute from the other alternatives until there are no remaining gains from substitution.

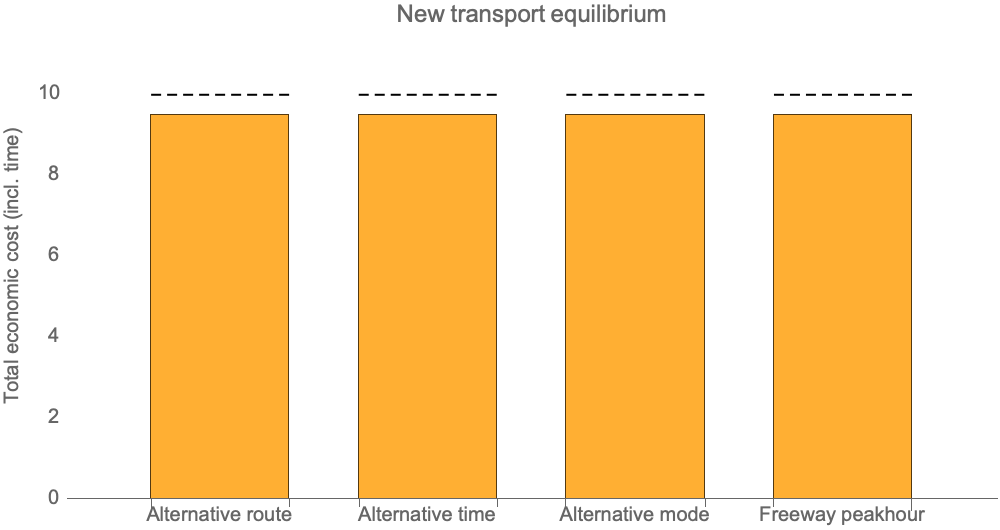

Afterwards, the new equilibrium looks like this. I’ve put a dashed line at the old equilibrium to show that there can be overall gains from expanding transport capacity, even though they are not observed in the option that received the investment.[1]

How much below the previous equilibrium the cost profile of the transport alternatives remains depends on how much these costs can adjust downwards and the preference for substituting towards non-transport uses of time and money.

For example, if alternative transport modes have a fixed cost (e.g. taking the train in peak hour has a fixed price and time cost that does not change based on usage), then the new cost equilibrium will occur at the same level as previously. That fixed cost of the alternative mode will anchor the equilibrium time and cost level at which these options equilibrate.

This is what is meant by the observation that “the equilibrium speed of car traffic on a road network is determined by the average door-to-door speed of equivalent journeys taken by public transport.”[2]

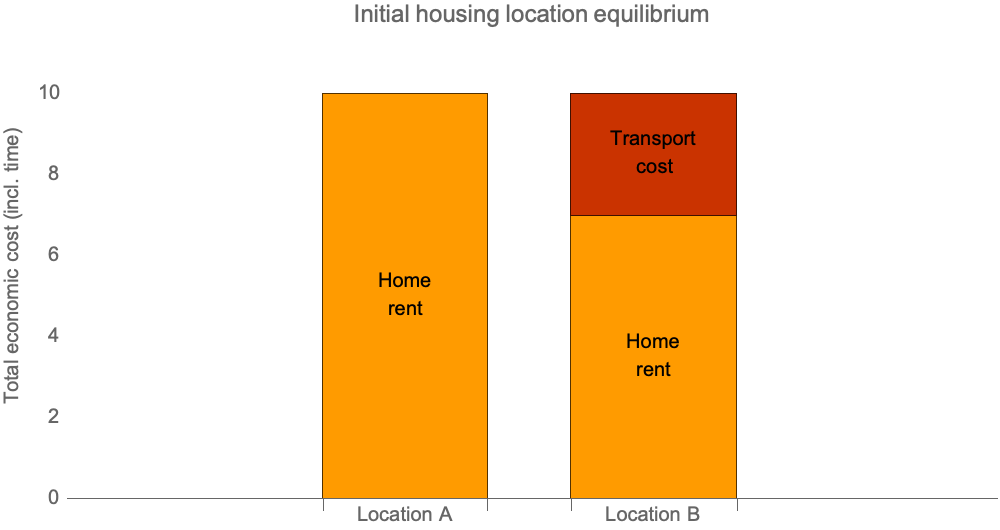

Similar margins of substitution happen in housing. Housing is another spatial allocation problem where the cost involves a trade-off between price and time costs amongst alternatives.

Location alternatives are one such margin. Total cost equilibrates, via rent adjustment, between comparable dwellings at alternative locations based on relative transport/accessibility costs.

When the transport/accessibility cost of a location falls, the rent in that area rises so that there are no gains from substitution between locations.

Another margin of substitution in housing is between modes, like renting and buying. When the cost of some buying goes up, it can drag up the cost of renting as market participants close the gap between buying and renting. Alternatively, if the cost of renting falls, it tends to pull down the cost of buying.

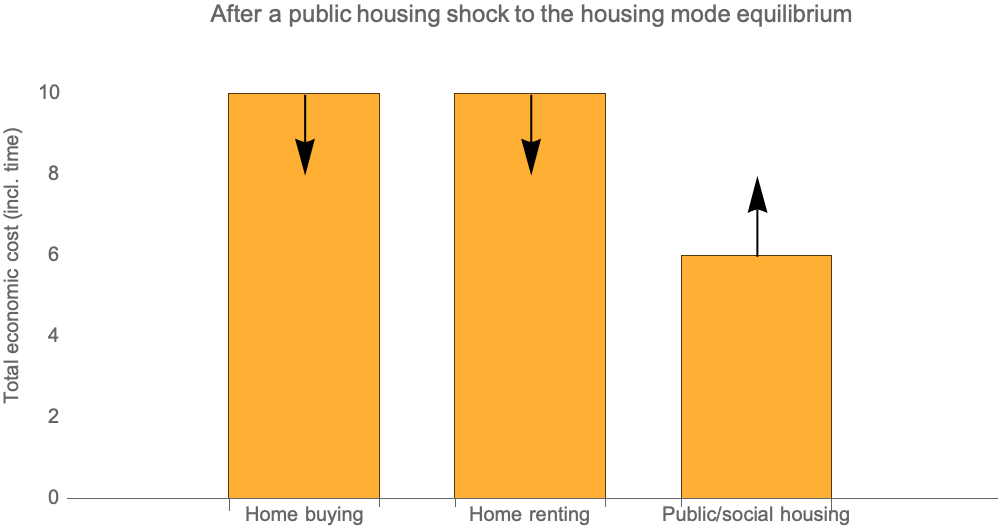

What if there is another alternative housing mode? Say, a social or public housing option that has a fixed price. In this case, the point at which there is no substitution between them is where they all have the same economic cost.

If the cost of public housing falls, this puts pressure on the housing equilibrium. Homebuyers and renters begin substituting to this cheaper alternative, just like the case of the new freeway in transport equilibrium.

This substitution process continues until there are no gains from substituting between housing modes. Public (non-market) housing alternatives can create an anchor for prices, just as public transport alternatives anchor congestion levels.

One could argue that “the equilibrium price of housing in a private market is determined by the average price of equivalent public housing.”

Our policy choice not to extensively provide cheap housing alternatives has allowed housing prices to be anchored by the maximum willingness to pay in the market rather than the cost of public housing.

The DT paradox is why places with low traffic congestion are usually those that have good alternatives. It is also why places with cheaper private housing markets have cheaper and more widely available non-market alternatives.

[1] This is actually how monetary policy works. The overnight cash rate is manipulated, and then all the alternative interest rates shift because there is a substitution between the overnight rate and long-dated assets.

[2] The D-T paradox has implications for pricing choices on transport networks. For example, peak-hour congestion charging will raise the cost fo driving, creating substitution to alternatives, including the alternative of not travelling. When a new rail line is built to relieve pressure on roads, tickets must be priced low enough to attract people towards that alternative and away from road travel. If new rail lines are privately owned and earn a return from ticket sales only, they have an incentive to maximise their own revenue, but this may involve a ticket price that is too high to maximise overall transport gains by attracting more substitution away from road travel. New toll roads also are likely to over-price compared to the optimum for the network as a whole that would see more substitution to these new roads.

Subscribe to Fresh Economic Thinking

New ideas and analysis by Dr Cameron K. Murray