Discover more from Fresh Economic Thinking

Did public housing create the Australian dream?

The free market did not boost homeownership from 35% to 72%.

Homeownership is the Australian Dream, just like it is the American Dream, the Canadian Dream, the British Dream and the Kiwi Dream.

How did that come to be?

Australia’s pre-WWII homeownership rate in urban areas was 46% and about 35% pre-WWI. It increased from 46% to 72% between 1947 and 1966. Similar increases in homeownership happened in the United Kingdom and the United States during and after WWII.

For most of that post-war period of rising homeownership, there was a Liberal-Country federal government under Prime Minister Robert Menzies (1951-1966).

In his earlier 1949 campaign speech, Menzies explained how he wanted people to own their own homes and be “little capitalists”, and he later showed he was willing to spend plenty from the federal government budget to make that happen.

Except in relation to the Territories and War Service Homes, the direct responsibility for housing is with the State Governments. But the Commonwealth must accept large obligations of assistance. There is already a Commonwealth-States Housing Agreement. We will seek its amendment so as to permit and aid ‘little Capitalists’ to own their own homes.

This was the opposite position of the previous Labor government. Here’s Labor Minister John Dedman in an exchange with Country Party MP Larry Anthony.

DEDMAN: The Commonwealth Government is concerned to provide adequate and good housing for the workers; it is not concerned with making workers into little capitalists.

ANTHONY: In other words, it is not concerned with making them homeowners.

DEDMAN: If there is any criticism which may be directed against the policies of past governments supported by the present opposition; it is this: too much of their legislative program was deliberately designed to place the workers in a position in which they would have a vested interest in the continuance of capitalism. This is a policy which will not have my support at any rate."

This was later pounced on by Anthony.

The minister for Postwar Reconstruction said the legislation to enable workers to own their own homes would create a lot of little capitalists and that would retard the onward march of socialism. That was a most extraordinary statement. Does it mean that the policy of the present government is to discourage home ownership?

This political wedge is why Australia’s grand public housing schemes of the era were ultimately pro-homeownership. Much of the publicly-built housing was sold to tenants at discounted prices, and other schemes existed to provide land for first-home buyers at cheap prices so they could build their homes using publicly-provided discounted financing at high loan-to-value ratios.

By his 1955 re-election speech, Menzies boasted about how much the federal government had done to fund new home building.

In their five post-war years, the then Labor Government saw 202,000 houses and flats completed in Australia. This was good. In our five completed financial years, 388,000 houses and flats have been completed; a record unsurpassed anywhere.

In War Service Homes, the Labor Government’s five-year record was 22,755 homes, our five-year record 68,162!

We have, in fact, during 5½ years, provided nearly 20,000 more War Service Homes than were produced under all previous administrations for the previous 30 years since the inception of the scheme.

But we look forward. The housing arrears, accumulated during the war, are being handsomely reduced.

But there remains the vital problem of home ownership. In April we passed a law enabling tenants of houses built under the commonwealth and States Housing Agreement to buy those houses on favourable terms.

We have now proposed to the States that there should be a new Housing Agreement under which the Commonwealth will provide further moneys at a favourable rate of interest; on condition that at least 20 per cent of these housing moneys should be made available for home purchase through building or co-operative building societies or other institutions approved by the commonwealth.

The way Menzies got the huge boost to homeownership he desired was by pouring federal money into building a lot of homes and providing people with discounted ways of buying them. Predominantly, this was through the purchase of housing commission dwellings and funding for state-run housing developers who sold only to first-home buyers at discounted prices. He didn’t rely on the market, nor think that upzoning or fancy tax tricks would get high homeownership. He knew that governments had to operate on the supply side of the market and provide access to those homes below the market price.

In those years 15% of new dwellings were built by public housing agencies.

To translate that period to today’s numbers, 15% of all new housing would be about 25,000 to 30,000 new public dwellings per year. Another boost of 20 percentage points in homeownership, like those postwar decades, would get us from 66% to 86% homeownership, near Singapore’s level, and take over two million households out of the rental market.

The scale of change in that era when it comes to housing outcomes is hard to fathom today.

A common criticism of proposals to learn from the past and enact major public housing schemes today is that the buildings themselves are terrible and they concentrate poverty, creating slums.

Sure, you can do public housing with poor quality buildings and give that housing only to the poorest. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Australia also has a record of excellent public housing programs.

Historically, public intervention in housing was often done to eradicate slums by providing housing of adequate quality to households who couldn’t otherwise afford it — a waterproof roof, windows for light access, and running water. And indeed, this went hand in hand with reducing the concentration of poverty in slums that private markets were creating.

Some of the housing built in the post-war era is extremely desirable now. I remember in 2002, or thereabouts, looking to buy publicly built housing in Keperra, Brisbane. These homes were solid, low maintenance, and hence a very desirable investment. Homeowners who bought these homes originally through public home-purchase schemes had many decades of low fuss cheap and desirable housing.

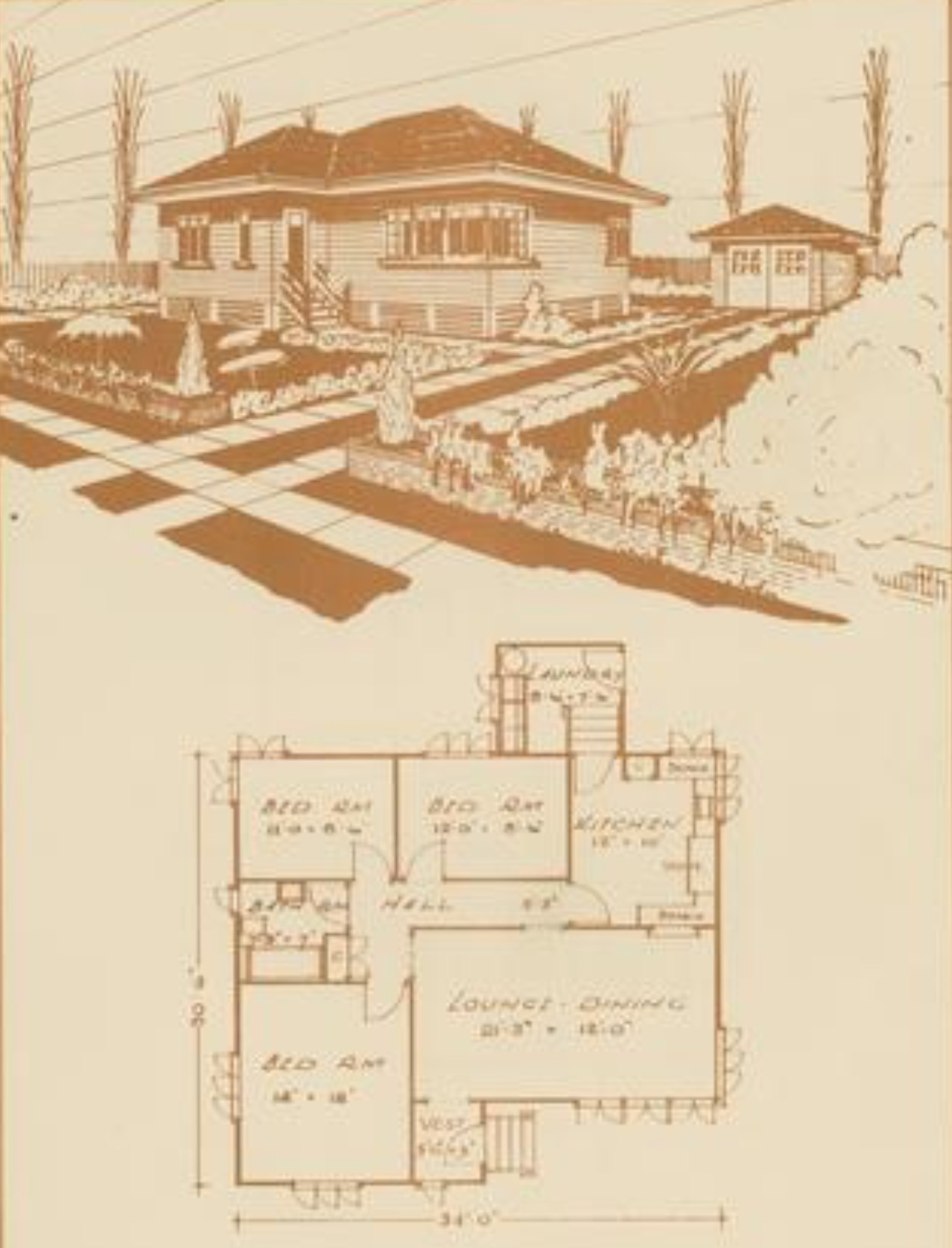

NSW Housing Commission had an extensive construction program in the post-war period, and as you can see from their 1954 annual report, a built range of dwellings in a range of locations, something that could be easily replicated today. They even built harbour view apartments all around Sydney that are still owned by the state agency and provide cheap housing to tenants today.

The legacy of high homeownership from that era has lasted generations. Public housing agencies today have also inherited hundreds of billions of dollars of property assets from these seventy-year-old programs. But for some reason, despite ongoing debates and concerns about the high price of housing for young and low-income households, we seem to do our best to ignore our own past and ignore the policies that created the Great Australian Dream in the first place.

Which just leaves the question of why there is no revival of this sort of conservative social-democracy? There is plenty of history to build on, plus what I'm sure is a keen electoral base to mobilize, but no takers in the political class beyond a teal or two.

"The home is the foundation of sanity and sobriety; it is the indispensable condition of continuity; its health determines the health of society as a whole."

https://www.menziesrc.org/the-forgotten-people